‘Statute’ in ‘the Interpretation of statutes’ refers to the statutory laws made by the legislature that is the parliament or the state legislatures. A statute is said to be the will of the legislature. The parliament cannot judge cases on an individual basis so their general intent on what the law should be is passed through a form of text or more precisely an Act.

This Act is published by the government on the Official Gazatte i.e a public journal and made available to all. Once the Act receives the assent of the president, published and notified, it becomes law.

There are three broad functions of the government: the Legislative which makes laws, the executive which implements laws, and the Judiciary which interprets laws. These heads are independent of each other and this separation of power maintains a fair system of administration.

What does Interpretation of Statute mean?

It may so happen that these Acts or laws made by the parliament are ambiguous in nature or it may miss out on something, it could even be confusing.

A lot of time same things are perceived by different people in different ways, which is unavoidable and in human nature.

Situations may arise when these laws need to be applied and to remove these semantic difficulties the courts shall have to apply the general principles of interpretation to come to a conclusion.

What are the General Principles of Interpretation?

At the outset, it must be noted that it is only when the intention of the legislature is not clear, these principles of interpretation of a statute must be applied.

Since our legal system is by and large built up from Common law, our principles of Interpretation are also the same as the common law system.

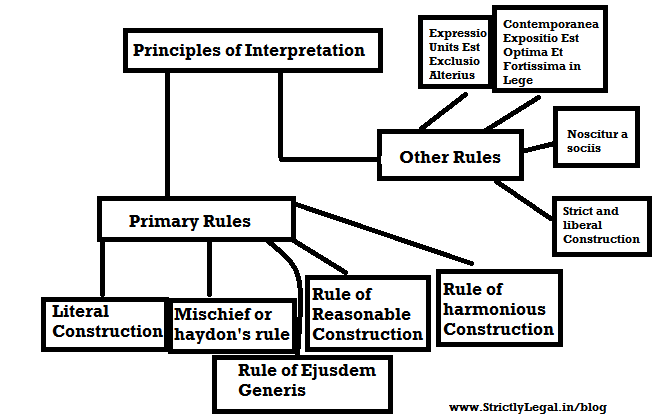

The general principles can be classified into two types:

- Primary Rules and

- Other rules of interpretation.

Primary Rules for Interpretation of Statutes

Literal Construction

The rule of literal construction states that words, phrases, and sentences in the statute must be ordinarily be understood in their grammatical, literal, and ordinary meaning unless such an interpretation leads to absurdity.

The safer and more correct way of dealing with interpretation is to arrive at a decision as to

- Every word used in a statute should be given meaning and no word is used unnecessarily.

- One should not presume any omissions, if a word is not there in the statute it cannot be given a meaning.

What does the SC say about the rule of literal construction?

One of the basic principles of interpretation of statutes is to construe them according to plain, literal, and grammatical meaning of the words.

H.P v. Pawan Kumar (2005) 4

— If that is contrary to, or inconsistent with, any express intention or declared purpose of the Statute, or if it would involve any absurdity, repugnancy or inconsistency, the grammatical sense must then be modified, extended, abridged, so far as to avoid such an inconvenience, but no further.

— The onus of showing that the words do not mean what they say lies heavily on the party who alleges it.

— He must advance something which clearly shows that the grammatical construction would be repugnant to the intention of the Act or lead to some manifest absurdity.

SCALE, P.1

The Mischief Rule or Heydon’s Rule

The mischief or the Haydon’s rule states that four essential things are to be recognized and considered while interpreting a statute:

(1) What was the Law before the making of the Act;

(2) What was the mischief and defect for which the Law did not provide;

(3) What is the remedy that the Parliament had resolved to; and

(4) The true reason for the remedy.

When the material words, sentences, or phrases are capable of bearing two or more constructions, the most well-established rule for the construction of such words is the rule laid down in Heydon’s case.

It has “now attained the status of a classic”. The rule directs that the Courts must adopt that construction which “shall suppress the mischief and advance the remedy”

What does the SC say about the Mischief rule or the Haydon’s case?

The Supreme Court in Sodra Devi’s case, AIR 1957 S.C. 832 has expressed the view that the rule in Heydon’s case is applicable only when the words in question are ambiguous and are reasonably capable of more than one meaning.

Sodra Devi’s case, AIR 1957 S.C. 832

The correct principle is that after the words have been construed in their context and it is found that the language is capable of bearing only one construction, the rule in Heydon’s case ceases to be controlling and gives way to the plain meaning rule.

Rule of Reasonable Construction

Ut Res Magis Valeat Quam Pareat in English it translates to It is better for a thing to have an effect than to be made void.

According to this rule, the words of a statute must be construed ut res magis valeat quam pareat, so as to give a sensible meaning to them.

A provision of law cannot be so interpreted as to part it entirely from common sense; every word, sentence, and phrase or expression used in an Act should receive a natural and fair meaning.

It is the duty of a Court in constructing a statute to give effect to the intention of the lawmakers i.e the legislature.

If therefore, giving of literal meaning to a word used by the legislature particularly in the penal statutes would defeat the very object, which is to suppress mischief, the Court can depart from the dictionary meaning which will advance the remedy and suppress the mischief.

It is only when the language of a statute, in its ordinary meaning and grammatical construction, leads to a manifest contradiction of the apparent purpose of the enactment, or to some inconvenience or absurdity, the hardship of injustice, presumably not intended, a construction may be put upon it which modifies the meaning of the words and even the structure of the sentence

(Tirath Singh v. Bachittar Singh, A.I.R. 1955 S.C. 830

Rule of Harmonious Construction

It is the responsibility of the Courts to avoid “a head-on clash” between two sections of the same Act,

“whenever it is possible to do so, to construct provisions which appear to conflict so that they harmonize”

(Raj Krishna v. Pinod Kanungo, A.I.R. 1954 S.C. 202 at 203

In other words, a lot of time it may so happen that two sections of the same Act may appear to be conflicting with each other,

In circumstances like these, it is the rule of Harmonious Construction that is to be applied so that both the sections can be read together and given effect to as far as possible.

Rule of Ejusdem Generis

Ejusdem Generis in English translates to “of the same kind or species”.

Where there are general words following particular and specific words, the general words following particular and specific words must be restricted to things of the same kind as those specified, unless there is a clear indication of a contrary purpose.

For example, In Ashbury Rly Carriage and Iron Co Ltd v Riche, it was held that the word ‘other contracts‘ in ‘Engineering and other contracts‘ means contracts relating to engineering only and does not include contracts of financial nature.

The rule of ejusdem generis must be applied with great caution because, it implies a departure from the natural meaning of words, to give them a meaning or assumed intention of the legislature.

This rule must be controlled by the fundamental rule that statutes must be construed to carry out the object sought to be accomplished.

Whether the rule of ejusdem generis should be applied or not to a particular provision depends upon the purpose and object of the provision which is intended to be achieved.

Other Rules of Interpretation of Statutes

Expressio Unis Est Exclusio Alterius

The rule means that express mention of one thing necessarily implies the exclusion of another.

For example, if the statute states that Ice-cream shall only mean vanilla flavored ice-creams then any other ice cream ( suppose, chocolate flavored) would not be considered under the definition of ice cream.

Contemporanea Expositio Est Optima Et Fortissima in Lege

This maxim in English translates to contemporaneous exposition is the best and strongest in law i.e where the words used in a statute have experienced alteration in meaning in course of time, the words will be interpreted to bear the same meaning as they had when the statute was passed.

In simpler terms, old statutes must be interpreted as they would have been at the date when they were passed. That is Interpret their old meaning.

Noscitur a Sociis

The rule of Noscitur a Sociis indicates that the meaning of a word should be known from its accompanying or associating words. It is not a sound principle in the interpretation of statutes, to emphasize one-word disjunct from its preceding and succeeding words.

A word in a statutory provision is to be read in collocation with its companion words to come at a wise interpretation.

Strict and Liberal Construction

Strict and liberal construction are opposite in their nature.

In strict Construction, statutes are interpreted in a very narrow and strict sense so as to exclude everything that is not contained in the statute’s letter as well as spirit. Whereas Liberal construction is as its name suggests, a very liberal way of interpretation so as to “everything is to be done in the advancement of the remedy..”

FAQ

Tnterpretation of statutes is a common law principle and is not a codified law. Therefore, it has no bare Act.

Sometimes the legislation may be unclear, confusing, or interpreted in many ways by many people. To put a distinct meaning to the statute or any provision of law the courts would have to deal with it using the principles of interpretations.

Interpretation of statutes contains various rules, Harmonious construction, literal construction, the rule of ejusdem generis, mischeif rule, etc.

Conclusion

“Although the literal rule is the one most frequently referred to in express terms, the Courts treat all three ways of Interpretation of Statutes (viz., the literal rule, the golden rule, and the mischief rule) as valid and refer to them as occasion demands, but do not assign any reasons for choosing one rather than another.

Sometimes a Court discusses all three approaches. Sometimes it expressly rejects the ‘mischief rule’ in favor of the ‘literal rule’. Sometimes it prefers, although never expressly, the mischief rule to the literal rule.”

Passionate about using the law to make a difference in people’s lives. An Advocate by profession.

Interpretation of a statute is a great subject that I always love reading. This is one of those that never ends, you will never learn the perfect art of interpretation -that’s the saddest part